State of Play Report

Form follows function 01.1

The misunderstood maxim of the American architect and author Louis Henry Sullivan.

Form follows function 01.1

Everyone should be familiar with it to this day, the popular maxim of the American architect and essayist Louis Henry Sullivan. Sullivan was an architect and author who thought and wrote a lot about the meaning and significance of architectural design and urban planning.

Louis Henry Sullivan

Source: Louis H. Sullivan, Wikipedia

By beauty I mean the promise of function; by action, the presence of function; by character, the memory of function.

Introduction

Subject:

The theme of the work is the quote by the American architect and essayist Louis Henri Sullivan, which is still well-known today. Sullivan's main creative period almost coincides with the turn of the century, a time when society and the arts were undergoing rapid changes. An ideological slogan from this period has survived to this day, which has retained its vibrancy and topicality, especially among designers, but also among architects.

Aims

What is behind this inconspicuous phrase 'form follows function', which can be translated as 'form follows function'? What kind of person and architect was Sullivan? What was Sullivan's motivation for this idea? What were the reasons for his idea of the dependence of form? Were there any artistic, social or technical currents in his time that prompted him to develop this idea?

To what extent does Sullivan himself deal with his demand in his artistic work; do his buildings deliver what his wishes and demands promise?

From today's perspective of the historical context; how is his formulation, his idea to be understood; to which products can his ideology be applied, to which not?

Are there products in which his ideology has been successfully put into practice?

Timeline Louis H. Sullivan

1855 5. September Louis Henri Sullivan is born in Boston, Massachusetts, the son of Andrienne Sullivan (née List) and Patrick Sullivan.

1860-70 Attends grammar school in Boston.

Writes, among others, A System of Architectural Ornament.

1870 High School Boston.

1872-73 Attends architectural lectures at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Draftsman in the office of Furness and Hewitt in Philadelphia; moves to Chicago, works for William Le Baron Jenney.

1874 Returns to Chicago, finally employed in the office of Dankmar Adler.

1876-79 Rückkehr nach Chicago, schließlich Anstellung im Büro Dankmar Adler.

1881 Adler/Sullivan partnership; for the next 12 years this architectural firm was the most active in Chicago; from 1880-1895 Sullivan designed more than 100 buildings.

1893 Transportation Building, Chicago World's Fair.

1895 Dissolution of partnership with Adler.

1895-1924 Sullivan works alone, numerous writings, including A System of Architectural Ornament.

1924 Louis Henri Sullivan dies on 14 April in a hotel room in Chicago.

My theory of building is as follows: A scientific arrangement of spaces and forms in adaptation to function and place; emphasis on elements proportionate to their importance in relation to function; colour and ornamentation must be determined, unconstrained and varied according to strictly organic laws, each individual decision to be justified precisely; immediate banishment of all fiction.

Situation

Jeffersonian democratism

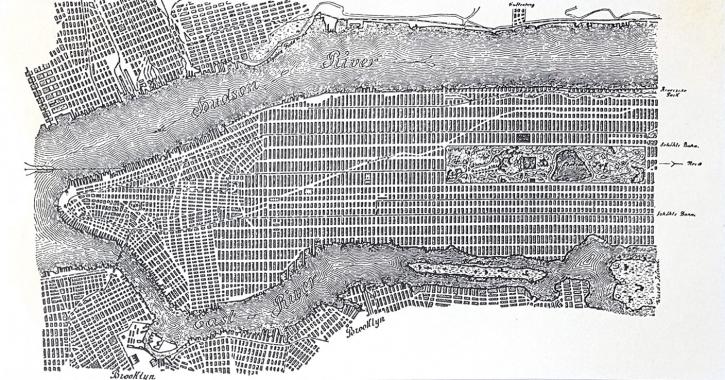

The increasing industrialisation and the rapidly growing urban population in North America at the beginning of the 19th century made it necessary to develop new forms of urban planning and urban design. Here, too, what is still today a democratic principle for the coexistence of American citizens, coined by the president and architect Thomas Jefferson, was to apply to the planning of a large city. Thus the "Plan of New York ... roughly comparable to the American Constitution, in which the rules of political coexistence are formulated in such a way as to impose a minimum of restriction on the initiative of citizens, and for this very reason they are reduced to a set of formal provisions, the meaning of which can only be understood in connection with the use that has been and is still being made of them." (Source 4)

The New York Plan

In 1811, the Morris Commission developed a checkerboard plan (Fig. 1) for the city of New York, which divided a huge area uniformly and at right angles, without perspective or orientation, into equal-sized lots, on which could now be built what was needed, dwellings, offices, supermarkets, administrative buildings, theatres, etc.

In order to understand this urban planning pattern, one has to look back to the American colonial era, when the American continent was also divided into uniform, rather angular plots, taking into account longitude and latitude. States that were not yet known and therefore could not be given a natural, cultural or functional shape had to be divided up for settlement. Just as it was not yet possible to foresee or anticipate the development of the states, it was also not possible to do so in the planning of cities, and likewise not in the planning of enormous high-rise buildings. Since no use was known, since it was not possible to look into the future, the states, cities and buildings were given forms that could later contain anything, industry, offices or flats. The plan was at the same time very precise, in that it divided the area of the city with orthogonal streets ("... and if the streets intersected at right angles, the houses would be less expensive to build and more comfortable to live in") into uniform plots, on the other hand it left the use of these small areas completely open. "What objects are to be placed on the individual building plots is neither said nor determined in advance, practically they can change at any time; unchanged, however, is the chequered subdivision of the land in a given unit of measurement, as well as the fixed numbering of each field ..." Source 6.

Since one does not know how a district will develop, one does not assign any particular functions to it, in its perfect order the plan becomes a disorderly city in its real implementation, since "the modern city does not consist mainly of dwellings, but of many other things: Railways, markets, department stores, offices, hospitals, theatres, cinemas, car parks and so on, all of which have different dimensions and requirements."

Although these city plans evoked a host of problems that can be studied today on the "living" object, from them "one of the most essential traits of American tradition becomes visible. Some elements are rigidly and unalterably fixed, but only so much as is necessary to have a common and undisputed point of reference, on which basis everything else can unfold freely and uninhibitedly" Source 8.

Perhaps the plan of a city, obeying neither baroque perspective nor chaotic, urban labyrinthine laws of origin, in a sense anticipates the plan of a skyscraper. The skyscrapers first built in North America a little later were also structures made up of uniformly shaped rooms (surfaces) of the same size, which were held together by constructive rules but not by rules that created meaning and order. Here, the large demand for office space meant that it had to be made available en masse, but now a small and expensive building site had to be somehow spatially divided into equally sized rooms (plots). Thus, floor after floor was uniformly placed on top of each other, whereby an attempt was initially made to retain the classical structure of a building by having the many floors rest on a foundation supported by arches and crowning the entire building with a Romanesque-inspired gable.

Chicago

At the time Louis H. Sullivan began his studies at MIT, Chicago, which was predominantly built of wood, was almost completely destroyed by fire in 1871.

The reconstruction of the city, which progressed only hesitantly at first, was intensively promoted between 1880 and 1890, and the city boomed. Increasingly expensive land prices in the centre of the city meant that only the construction of office buildings made sense. The advancing industrialisation wanted to be managed. One of the most important tasks of the architects of this time was the construction of office and commercial buildings. The work of architects of this period, including W. Le Baron Jenney, W.W. Boyington, D.H.Burnham, J.W. Root, W. Holabird, M. Roche and L.H. Sullivan, is of a distinctly uniform character, especially in one Chicago neighbourhood, the Loop. The task of building new office and administrative palaces was taken up enthusiastically by the architects of the time. Le Baron Jenney perfected the steel skeleton, which for the first time made it possible to build greater heights without having to excessively reinforce the columns in the lower areas. Many of the artists had studied in Paris, as there was no architectural training in the United States at the time, so an "institute like the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, which is generally regarded as conservative, ... Architects who understood the grand style and at the same time took advantage of the latest advances in building technology." Source 9.

In addition to the constructive structural innovations, it was other, typically American inventions that drove the construction of the multi-storey skyscraper.

"If the halls owed their room widths to the tensile material, the steel skeleton construction, together with new building installation technology such as lifts, electrical supply, telephones, air-conditioning and sanitary facilities, also helped to develop the height. Here, as there, mass was replaced by lines and points, namely by bar-shaped elements, node-shaped connections and point-like load transfers" Source 10

The architects had learned at the Paris École to achieve impressive effects, "but also to pay attention to rational planning. Editor's note]" The ground plan was the starting point - so much so that a famous teacher at the Ecole, Victor Laloux, had his students draw the façades last. Traffic routes within the building were given special attention, even if it was not a matter of economic routing, but of imposing sequences of rooms. Even the requirement that the internal purposes should be reflected in the external volumes played a role. Source 11.

Like the chessboard plan of a large city (New York), the American skyscraper is also a typically American, abstracting process; the function of architecture, of building art, is therefore no longer seen only in terms of form and design.

The design of a skyscraper is an arithmetical ope ration and, as F. L. Wright once said, "a mechanical device to increase the number of building sites that can be sold and resold as often as it is possible to sell the original site". Source 12. The skyscraper was a way of bringing architecture into line with the demands of industrial society.

The skyscraper

In 1890, for the first time in the world, an office building rose up to 16 storeys, supported entirely by a steel skeleton, albeit clad in stone. The problem for the architects of the time was that the skyscraper contained previously unknown architectural and formal elements that could not be solved with the architectural means available at the time. Classical structuring of a building could not be applied to a building that consisted of the same, repetitive elements over and over again. New technical functions, new installation techniques and operating systems such as lifts, which only made it possible to traverse the stacked floors quickly and rationally, and air-conditioning systems, which made it possible to ventilate large enclosed office floors, were new challenges for the architects of the time, and they met them only to a limited extent, as Gréber wrote in 1920: "Originally, a commercial building was supposed to look like a simple block, equipped with office cubicles (loft) and crowned by an ornately crafted cornice.

Its exterior was, so to speak, a caricature of its inner purpose. The shortcomings of this deliberate lack of architectural circumspection were accentuated by the appearance of numerous operational installations on the roof terrace, reservoirs, lift cabins, ventilation systems, etc., which were supposedly hidden from view, but in reality could by no means be adequately concealed; these mechanical parts sometimes contrasted quite naively with the Florentine-style façades. The great progress that was subsequently made in the construction of commercial buildings was that the distributive programme was exploited architecturally and tower buildings were erected, the tops of which served to protect and camouflage the operating equipment, which greatly benefited the appearance of the building. The great problem of too many windows, which from a distance make these blocks look like huge honeycombs, was quite happily solved by grouping the windows vertically by means of strong ribs, which emphasise the vertical and therefore also the imposing aspect of the tower". Source 13

These formal possibilities mentioned here were not yet available to Chicago architects before the turn of the century. Individual experiences of the individual architects initially seemed to promote a development towards a new style of architecture that met the requirements; the success of the neo-classical Chicago World's Fair of 1893 caused this development to suffer a setback; Louis H. Sullivan, whose work was characterised by a very personal view that was attached to nature, also suffered the consequences of the exhibition because he was not prepared to adapt to the wishes of the clients. Sullivan also once described the work of the other architects "as perverse, in that they used the steel-frame function in a masonry form; how grotesque this was is best understood by trying to imagine horse-eagles or tarantula potatoes". Source 14.

Beauty does not come by lawful command,

nor will history,

as it happened in Greece,

will be repeated in England or America.

It will, as always,

without notice.

and blossom in the footsteps of brave

and serious people. 15

Louis H. Sullivan

Influences

Sullivan's literary and architectural work expresses a desire to combine technical science with romantic nature. During his childhood and youth, Louis H. Sullivan spent his time alternately in the countryside

in the country and in the city. He began to spend his time in the countryside studying nature and discovering the mythical in nature, while the city served him to discover the possibilities of human creativity, observing the work in a shipyard; bridges and, from the age of 12, architecture, interested him. Perhaps it was this ambivalence of his nature-loving and technology-interested life that led him to become so interested in architecture and building in his studies, first at MIT and later at the École des Beaux Arts. Even as a boy he was fascinated by bridge building; according to his biography, he was disappointed when a bridge was not as elegant as he imagined. "Why couldn't a bridge accomplish its task with pride?" Source 16

Essential insights of his training in Paris were the ability to animate history, to begin a proof in scientific works with a personal assertion, to which the realisation prevailed that architecture was nothing fixed, but flowed incessantly from the infinite imagination of man, caused by his needs, and to these it was necessary as an architect to take into account. Architecture follows function, a function that depends on the wishes of the people who live, work and use a building.

Activity

Sullivan returned to Chicago four years after the Great Chicago Fire. The situation he found was characterised by a proliferation of the city on the periphery and a densification of the city in the centre. The centre of the city, destroyed in 1871, served as a building site for the most important architectural firms of the time. Chicago, like the whole of the eastern United States of America, was in a phase of economic upswing. The architects were characterised by a good technical education, but at the same time they lacked the binding, constantly present architectural tradition of their colleagues in Europe. At the time Sullivan started working in a Chicago office at the age of just over 18, Le Baron Jenney was erecting his first all-steel skeleton building; in the centre of Chicago, a huge open space was being built on in a concentrated way; new technical developments were influencing the function and construction of a building. The still young American tradition of prefabricated construction, which originated in timber construction, is perfected in steel skeleton construction.

In 1864 the first steam-driven lift appeared, followed by the first hydraulic lift in 1870 and the first electric lift in Chicago in 1887. At first Sullivan worked for the plant manager of Le Baron Jenney. "He expanded Sullivan's idea of function, dwelling at first fleetingly on the study of botany, on the explanation of his own theory of suppressed functions - the psychological and metaphysical causes of the drives (as Sullivan also called function) that made forms necessary." Source 17

Since a new architectural style did not have to be developed for each project, the projects could be broken down into any number of individual parts. There was a strong division of labour in the offices. Sullivan became a partner in Dankmar Adler's office;

Adler was an architect for whom a building was primarily a technical problem and a financial matter. Unlike Adler, Sullivan was a lover of the fine arts, music and poetry, but above all felt he had to build very differently from his contemporaries. The first major project Adler and Sullivan planned together was the Auditorium Building, 1887, which at first seems a step backwards compared to the aspirations of local architects. The façade of the multi-purpose building is divided into four zones, and the arches, which become narrower towards the top, create a tapering perspective. The foundation is emphasised in its mass, the intermediate zone and the attic are integrated into the design of the façade (Figs. 5 and 6). Nevertheless, the façade, the building is not an image of its inner functional structure, but a division with the possibilities of eclecticism learned in Paris. W. J. Root writes about the inner structure and the social and economic constraints in designing the buildings: "It was worse than superfluous to waste an abundance of delicate ornamentation on them (the modern multi-storey delicate ornamentation on them (the modern multi-storey buildings) ... They had rather to convey with their mass and proportions, in an elementary exuberance of feeling, an idea of the great, enduring, preserving forces of modern culture. One result of the methods I have indicated will be the dissection of our building projects into their essential elements. The internal structure of these buildings has become so vital that it must necessarily determine the general character of the external forms; moreover, the commercial and constructive requirements have become so dominant that all the structural details which are intended to give expression to them must be modified accordingly. Under these conditions, we are compelled to work precisely and with precise objectives, to allow the spirit of the times to act fully upon us, so that we are able to give artistic form to its architecture" Source 18.

It is only later that Sullivan realises "that the composition in perspective is in a sense natural and consequently must be reconciled with the functional nature of the subject. He seems to have in mind an architecture determined by objective requirements, leaving to the imagination only the task of suggestively working out the fundamental features of the building. Later, however, when he studied the subject in greater detail, he realised that his theoretical description led him to an unprecedented mode of expression, while the recurring rhythm of the uniform storeys was incompatible with the closed composition resolved into foundation, intermediate zone and attic" , source 19.

Sullivan correctly assumes that the essence of a skyscraper is that it has many identical floors, all of which are uniform in design except for the one or two basements that form the foundation of the building. But if the number of mezzanines between the foundation and the roof is arbitrary, there can be no meaningful formal perspective division of the façade. "Above that, for the unspecified number of office corridors, we start from the single cell, for which windows, a sill, and an architrave are needed, and without worrying our heads any further, we give them all the same shape, since they all have the same function." Source 20.

The idea of the skyscraper logically leads to a completely new façade design without perspective, but this does not become established architecturally until much later, because an architect like Sullivan cannot consistently put his theory into practice. "... but the transition from theory to practice is dominated by a fundamental uncertainty which is ultimately the cause of his professional failure". Source 21

Decades later, Mies van der Rohe "revisits a possibility that had already been tried out by the masters of the Chicago School, dropped by Sullivan, and had since remained in the background: the concept of the multi-storey building not as a closed and perspectively uniform organism, which one tried to resolve by differentiating the various height zones and by accentuating the vertical ties, but as an open rhythmic organism, formed by the repetition of many of the same elements. This possibility makes it possible to eliminate at a stroke the compositional contrast between the scale of the whole and that of the details, since proportional considerations stop at the individual element; the overall composition depends on entirely different criteria, it does not withdraw from itself but relates to the infinite landscape ...". Source 22.

Nevertheless, Sullivan arrives at a very idiosyncratic and personal interpretation of the skyscraper. In his case, the idea of repeating the same floors and rooms leads to a strongly vertical orientation of the façade, as can also be seen in the Guarantee Building in Buffalo (Fig. 7).

In the case of the Carson, Pirie and Scott department stores', built between 1899 and 1904, Sullivan sees fit to repeat more than usual the uniformity of the repetitive façade elements and especially the windows. "Here the reticulated interior structure is projected quite simply to the exterior, without any vertical or horizontal constraint, and after the massing ratios have been relaxed, profuse decoration is applied, as in the juvenile works, to set off the foundation against the main body of the building." Source 23

The vertical and horizontal articulation established by the steel skeleton construction and the uniformity and sameness of the constructive and functional elements behind the façade are found again on the outside (Fig. 8). In his essay "The Large Office Building, Artistically Considered", Sullivan writes, in response to the criticism of his colleagues, in defence of his own ideas and with a certain doctrinal and missionary tone: "Every thing in nature has a form, that is, a shape, an outward appearance, by which we know what it means, and which distinguishes it from ourselves and from all other things. In nature these forms express the inner life, the innate value of the creatures or plants they represent; they are so characteristic and unmistakable that we simply say it is natural that they should be so. ... To him who stands on the shore of things and gazes steadfastly and lovingly where the sun shines and where, as we happily feel, life is, the heart is constantly filled with joy at the beauty and the informality with which life seeks and finds its forms - in perfect harmony with needs. Always it seems as if life and form were wholly one and inseparable, so complete is the fulfilment." Source 24

Ornament and detail

Looking at the buildings designed by Sullivan and constructed under his architectural direction, one is struck by the sometimes appliqué-like ornamentation. While in his early work the ornament seems to be an intergrative component, in which it appears to run in bands along columns and friezes, later it can be seen that the ornament stands out clearly from the background in terms of sculpture and colour. Sullivan seemed to use the ornament to summarise the spatial extent of a building into a whole. The ribbon-like ornamentation seems to support this. In his late works, especially the small-scale bank buildings in the Midwest, the ornament contrasts with the precision masonry behind it. It stands out conspicuously from it. Lauren S. Weingarden writes that Sullivan used ornament as a reference to nature as a source of artistic inspiration. It may, I believe, also have served a social and cultural function in the city, in that it (the ornament) served as a small-scale division of a façade that had a vivid dimension still visible to the pedestrian. Since it definitely has an ornamental function, Sullivan uses it to refer the viewer to nature. (see above)

At the same time, he counteracts the anonymity of building, develops his own system of ornamentation (A System of Architctural Ornament, 1922-24), causes the individual building to stand out from the mass of urban volume. "The rapid means of transport, such as railways and automobiles, and the hectic rhythm of a modern metropolis no longer permitted the contemplation of detail." Source 25. A building must be

be designed in such a way that, when viewed from any distance, a building can be recognised and perceived as an individual structure. Everyone knows this for themselves; with different and increasing speeds of movement, the ability to perceive details decreases. Perhaps Sullivan wanted to counteract this by designing the façade with the different viewing distances in mind? "It is the massing, the simple and easily grasped silhouette that will stimulate feeling and constitute beauty. The house appears only as a very small element of the street, ... and the street, for its part, is only a detail in the organism of the city". Source 26

Whether we think of the eagle gliding in flight, the open apple blossom, the heavy toiling draught horse, the majestic swan, the oak spreading its branches wide, the bottom of the winding stream, the drifting clouds or the sun shining above it all: form always follows function - and that is the law. Where the function does not change, the form does not change either. The granite rocks and the dreaming hills always remain the same; the lightning leaps into life, takes shape and dies in an instant. It is the law of all organic, inorganic, of all physical and metaphysical, of all human and superhuman things, of all genuine manifestations of the head, heart and soul, that life is recognisable in its expression, that form ever follows function. That is law. 27

“Form follows Function”

At first, Sullivan only referred to the office building with his ideology 'form follows function', which is still relevant today. His essay is at the same time a response to the criticism of his opponents, but also an exhortation and a call to do the same, to design under the premise that first of all the design of the function follows the form and finally, if the function remains unchanged, the form must also remain unchanged.

Sullivan transferred this ideology related to the design of an office building to design and architecture in general, as did countless other authors, design and architecture critics. In the Bauhaus, it was also true that the form of an object did not change if the material, production process and purpose did not change. This can be seen as an extended Sullivanian functionalism. The Duden dictionary writes the following about the term functionalism: "... exclusive consideration of the purpose of use in the design of buildings in the sun. For the Sullivan exemplary nature with renunciation of any purpose-unrelated deformation...". Source 28 The concept of function can include the most diverse parts, a product design or a building can fulfil a technical, an aesthetic, an ergonomic (product), a social, an economic, a political, a personal, an individual, an emotional, an ecological function, to name a few that come to mind.

The functionalism of the Bauhaus or the Ulm University of Applied Sciences often give the impression that only technical, ergonomic ("manual") and purpose-related functions of use play a role in design. Emotional, human functions seem to be left out.

Sullivan takes his understanding of forms from nature; he mentions animals, plants, mountains and lightning, the whole round of nature as we perceive it. And nature fulfils functions that buildings or products often cannot fulfil for us. We can relax in nature, live from it, among other things, because we drink water and eat plants and animals. We breathe air and live gratefully (hopefully) under the warming rays of the sun. For the Sullivan exemplary, we live with it, in it and from it; if it did not exist, life would die. In nature, as I understand Sullivan, there dwells a purpose, a meaning, of its own; immanent in all things is an inner function that expresses itself in their form. The linguistic devices, the form in which Sullivan expresses this and the images with which he works romanticise this image, but render it clearly and unmistakably.

I think I understand what he means, and I would like to reduce this to saying that nature is alive, and this life expresses itself in evolutionarily developed forms adapted to life. Whether this is a plant or an animal. Kay Bojsen once said: "Lines must smile. Life, blood and heart must be in things, and one should like to hold them in one's hand. They should be human, warm and alive". (Kay Bojsen) Source 29: Life must be in things, and the form depends on the function of this life. But it is not only the function that is reflected in the form, in my understanding it is also necessarily the life, it is emotions, radiations, activities connected with life that a form should show. Sullivan describes how the different tasks of an office building are reflected in the façade, in the outer form. The lower two floors have a special functional character, their form must differ from the form of the other floors. The difference is not only in the different activities carried out on the different floors (life), but also in the power and meaning given to each part.

Sullivan identifies an inner function of the building and derives a form from this inner life, adequate to nature. Is this law still applicable to the design of buildings and products today? Was and is this principle applied in architecture and design?

Current context

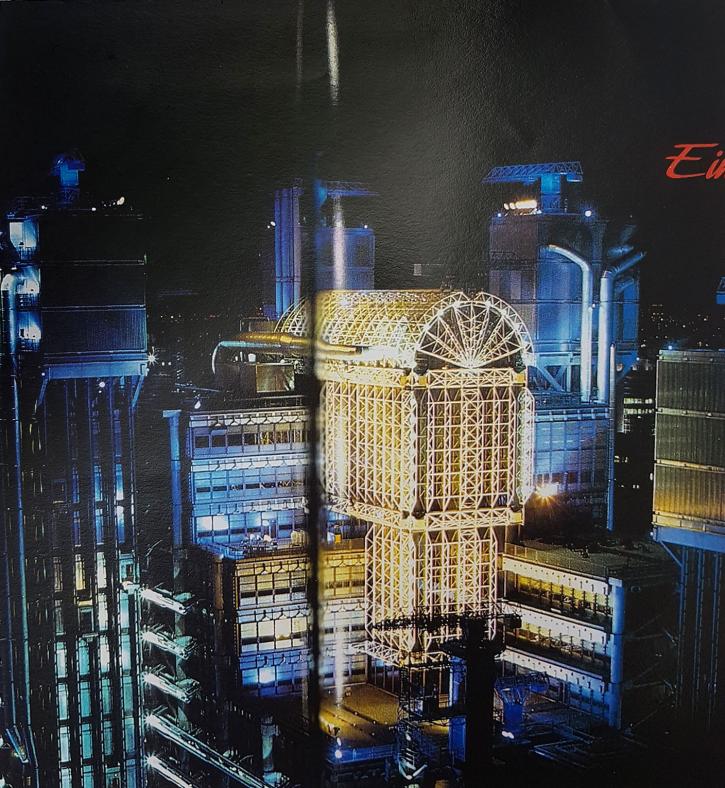

1. Example Lloyd's London

The Lloyd's London insurance market building, designed by the British architect Richard Rogers, shows its interior on the outside. Similar to the Centre Pompidou in Paris, means of transport are relocated from the inside to the outside, the lifts do not run inside but outside the building, all installations are also relocated here. The construction of the building is open, beams and other constructive elements can be seen, the individual parts of the building are given different, differentiated shapes. What cannot be seen is that this is the building of an insurance market, which parts of the building take over which functions, where which part of the company is housed. The form of the building says a lot about the technical structure, about technical functions, but at first glance there is nothing to be seen of the activities taking place inside and of a corresponding form. Nevertheless, the building is functionally divided into blocks. For Lloyds London, Sullivan's principle is valid, there is much to be seen of life, of the multiple functions that this form fulfils. (Fig. 11)

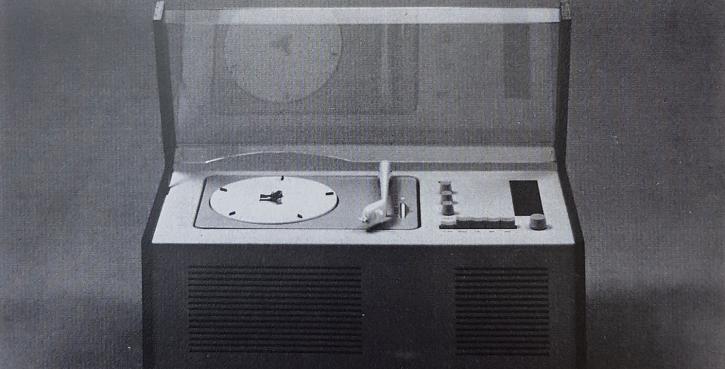

2. Example Braun design

The design of the appliances produced by Braun AG, Kronberg is subject to strict formal criteria. In the fifties and sixties, Braun design was regarded as the epitome of good product design. Sullivan wrote in 1896 that 'form follows function', meaning that the outer form follows the 'inner life' of a product. Whether it's the SK 1 radio (Fig. 12), the T 1/2/23 case transistor (Fig. 13), the SK 4/SK 5 phono super (Fig. 14), the atelier 1 hi-fi stereo system (Fig. 15) or the H 1 fan heater (Fig. 16) by Braun AG, what they all have in common is that you can't see what's inside, or you only know what's inside if you know the object beforehand. How is one to know that the first product is a radio, it could just as well be a measuring device or a control unit? This is true for many of the products depicted; the outer form is independent of the inner function. And life in the sense of Sullivan, i.e. an appeal to our feelings, cannot be a statement here for me personally.

3. Example of communication technology

A good example of the limits of Sullivanian ideology is the design of communication technology. The development from the old wall-mounted telephone with a speaking funnel and a loudspeaker funnel to the radio telephone of today is also accompanied by a development of forms that is becoming less and less comprehensible. A hundred years ago, people spoke into a funnel, a good formal synonym for 'entering' or 'coming out', whereas today it is an only slightly differentiated, rounded cuboid with a keypad. The mouth or sound opening is reduced to a tiny slit or a small hole. This product shows nothing of its inner life to the outside. The antenna may indicate that it is a device that emits electromagnetic waves, but nothing more.

The bell of a gramophone clearly showed what its function was, namely to amplify sound waves and radiate sound. Today, the acoustic boxes of a music system are mostly rectangular and cuboid-shaped boxes covered with fabric, and you can no longer see their inner workings.

What shape do you give a radio alarm clock that rings electronically and not mechanically with a bell? What shape do you give a computer that stores data that is different in every computer? What shape do you give a video recorder that plays and rewinds magnetic tapes?

These are many questions that could be continued at will, for there is a multitude of products whose electronic inner workings require no external form or an external form that is difficult to understand. It is the task of the designers to find a form for these products, a form that is not only oriented towards the technical and functional, but also towards the semantic function of a product, if this is necessary.